På senare tid har Global Voices visat sina läsare exempel på hur medborgarmedia används för att förstärka flyktingars röster [en]. Det är sant att bloggar och sociala media har en roll att spela i att öka egenmakten för marginaliserade grupper, men det gör också IKT i övrigt.

MobileActive uppmuntras t.ex. av mobiltelefonernas förmåga [en] att tillåta flyktingar att behålla kontakten med nära och kära, samt att få reda på var de befinner sig. En specialutgåva av Forced Migration Review [en] tittar närmare på användandet av IKT i detta sammanhang.

Flyktingar i Uganda använder SMS och mobiltelefoner för att kontakta familjemedlemmar och vänner. Foto från MobileActive

Refugees often experience a compound trauma: The situation that caused them to flee in the first place, as well as the fact that many families become separated during migration. For refugee's health and well-being and ability to resettle, it is vital to know the whereabouts of relatives, their safety, and their ability to remain in contact. Today, mobile phones are the most important technology for refugees to find relatives and remain in contact.

The Forced Migration Review Issue 38, The Technology Issue covers technologies for refugees in particular. Two chapters shine a light on the use of mobile phones among refugees, as well as some of the problems with this tech to find and contact family member such as issues of security, and accessibility.

Den 38:e utgåvan av The Forced Migration Review: The Technology Issue tittar på teknologier särskilt för flyktingar. Två kapitel upplyser om hur mobiltelefoner används bland flyktingar och problem som finns med teknologin för att hitta och kontakta familjemedlemmar samt säkerhets- och tillgänglighetsfrågor.

Deputy UN High Commissioner för flyktingar T. Alexander Aleinikoff bidrar med en introduktion till specialutgåvan [en]:

Superficially at least, today’s refugee camps do not appear significantly different from those that existed 30 or 40 years ago. Modernisation seems to have passed them by. But upon a closer look, it becomes apparent that things are changing.

Today, refugees and IDPs in the poorest of countries often have access to a mobile phone and are able to watch satellite TV. Internet cafés have sprung up in some settlements, the hardware purchased by refugee entrepreneurs or donated by humanitarian organisations such as UNHCR. And aid agencies themselves are increasingly making use of advanced technology: geographic information systems, Skype, biometric databases and Google Earth, to give just a few examples.

Idag har flyktingar och internflyktingar i de fattigaste länderna ofta tillgång till mobiltelefon och kan titta på satellit-tv. Internetcaféer har växt fram i vissa läger. Datorerna köps in av flyktingentreprenörer eller doneras av organisationer som UNHCR. Hjälporganisationerna själva använder mer och mer avancerad teknologi: geografiska informationssystem, Skype, biometriska databaser och Google Earth för att ta ett par exempel.

I en artikel beskrivs ett exempel med ett spårningsprojekt [en] som satts igång av Refugee Consortium of Kenya (RCK) i samarbete med Refugees United (RU):

In 1991 Ahmed Hassan Osman* fled the conflict in Somalia, leaving his family in Kismayu, and made his way to Kenya in search of asylum. Ahmed lived for a while in Ifo refugee camp before being resettled to Colorado in the US where he was granted full US citizenship.

In 1992, his cousin Abdulahi Sheikh arrived in Kenya in search of support. Granted refugee status, Abdulahi ended up in Dagahaley camp in Dadaab. He believed Ahmed was either in Dadaab or had been there but his efforts to find him were unsuccessful and he soon gave up hope of ever finding him. In fact, Abdulahi believed Ahmed had gone back to Somalia.

In early 2011 RCK employed Abdulahi to assist the RU project in Dagahaley refugee camp. Abdulahi registered with the tracing project and began a search for missing loved ones. Coming across a name that was familiar, he contacted the person through the RU message system. When he received a reply he realised that, after 20 years of separation and search, he had found his beloved cousin. They exchanged phone numbers and Ahmed called, breaking 20 years of silence. Today, the two keep in touch regularly and both Abdulahi and Ahmed continue to search for more friends and family members.

1992 kom hans kusin Abdulahi Sheikh till Kenya och sökte stöd. Han beviljades flyktingstatus och hamnade i Dagahaley-lägret i Dadaab. Han trodde att Ahmed var antingen i Dadaab eller hade varit där men hans försök att hitta honom lyckades inte och han gav snart upp hoppet om att någonsin hitta honom. Abdulahi trodde att han måste ha åkt tillbaka till Somalia.

Tidigt under 2011 anställde RCK Abdulahi för att hjälpa till med RU projektet i Dagahaley-lägret. Abdulahi registrerade sig själv i spårningsprojektet. När han såg ett namn som var intressant kontaktade han personen genom RU:s kommunikationssystem. När han fick svar insåg han att han, efter 20 års separation och sökande, hade hittat sin kära kusin. De bytte telefonnummer och Ahmed ringde och bröt 20 års tystnad. Idag har de kontakt regelbundet och både Abdulahi och Ahmed fortsätter söka efter mer vänner och släktingar.

Det finns förstås, vilket också MobileActive understryker, problem med den lokala infrastrukturen som utgör ett hinder för att liknande system implementeras [en]:

In some areas of Africa, there is no telecommunications coverage. Workshop participants commented that where it does exist, phone connections are regularly cut off, and some of them had also experienced intrusion in communication such as crossed lines. The strength of the network signal overseas is weak, and the lack of a reliable or steady source of electricity in a recipient’s country can be a major problem, although this varies by region. Growth of populations in some areas weakens network strength, due to the drain on power. Individuals may also have difficulty accessing electricity to charge their mobile phones.

[…]

Finding the best technology to use for different family members can be difficult, particularly if they themselves are displaced, because of factors such as the variety of available services, whether the family member could afford them and whether they have the skills to use them. One participant observed that the majority of their family members overseas needed to access communication technology through others. One participant described the difficulties she had in contacting her husband in a camp. She sent money to him to buy a phone but other people in the camp would also use it leaving her often waiting for hours to get in touch.

Cheap options such as email, voice-over-internet or instant messaging may not be accessible or affordable, and access to the internet in Africa is very expensive. Furthermore, displaced family members overseas may not know how to use these facilities.

[…]

Att hitta den bästa teknologin att använda för olika släktingar kan vara svårt, särskilt om de drivits bort, på grund av faktorer som de tjänster som erbjuds, om de har råd med dem och om de vet hur de används. En medverkande angav att de flesta av dennes släktingar var tvungna att använda kommunikationsteknologi genom andra. En annan beskrev hur hon upplevde svårigheter med att kontakta sin man i ett läger. Hon skickade pengar till honom för att köpa en telefon men andra i lägret använde den också, så ibland fick hon vänta i timmar för att komma i kontakt med honom.

Billiga alternativ som email, internettelefoni eller chattprogram kanske inte finns tillgängliga eller är för dyra, och internetanslutning i Afrika är väldigt dyrt. Familjemedlemmar som tvingats fly kanske också inte vet hur man använder internet.

Utgåvan ger en uttömmande översikt över hur IKT används, från att tillgodose flyktingars behov av tillgång till information om hälsovård och utbildningsmöjligheter till att använda Facebook, Gmail-chatt och Skype och till kontakter med släktingar och vänner över stora geografiska avstånd.

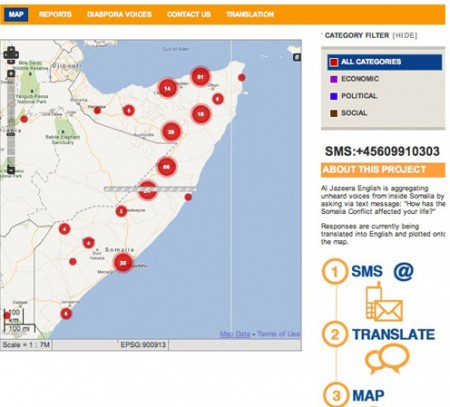

Ushahidi nämns också i samband med jordbävningen i Haiti 2010 [en] samt i allmänhet vad gäller konflikter, katastrofer och flyktingar [en]. PBS’ Idea Lab tar en titt på Al Jazeeras och Ushahidis samarbete för att förena och öka egenmakten hos somalier som separerats av konflikt och svält [en]:

Somalia Speaks is a collaboration between Souktel, a Palestinian-based organization providing SMS messaging services, Ushahidi, Al Jazeera, Crowdflower, and the African Diaspora Institute. “We wanted to find out the perspective of normal Somali citizens to tell us how the crisis has affected them and the Somali diaspora,” Al Jazeera's Soud Hyder said in an interview.

[…]

The goal of Somalia Speaks is to aggregate unheard voices from inside the region as well as from the Somalia diaspora by asking via text message: How has the Somalia Conflict affected your life? Responses are translated into English and plotted on a map. Since the launch, approximately 3,000 SMS messages have been received.

[…]

For Al Jazeera, Somalia Speaks is also a chance to test innovative mobile approaches to citizen media and news gathering.

[…]

Somalia Speaks mål är att samla ohörda röster från regionen och från diasporan genom att fråga “Hur har konflikten i Somalia påverkat ditt liv?” via SMS. Svaren översätts till engelska och läggs till på en karta. Sedan starten har ungefär 3 000 Sms-meddelanden tagits emot.

[…]

För Al Jazeera är Somalia Speaks också en chans att testa innovativa mobila användningsområden för medborgarmedia och nyhetsinsamling.

I oktober 2010 beskrev MobileActive också ett mobiltelefonbaserat projekt [en] implementerat av Refugees United i Uganda med stöd av Ericsson, UNHCR och the Omidyar Network, och noterade att en blogg kallade projektet “det sociala nätverket som är viktigare än Facebook”.

Teknologiutgåvan av Forced Migration Review kan läsas på nätet här [en].